1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

|

# Numerical Solutions of Ordinary Differential Equations

Fundamental laws of the universe derived in fields such as, physics, mechanics, electricity and thermodynamics define mechanisms of change. When combining these law's with continuity laws of energy, mass and momentum we get differential equations.

| Newton's Second Law of Motion | Equation | Description |

| ----------------------------- | -------------------------------- | ---------------------------------------------------- |

| Newton's Second Law of Motion | $$\frac{dv}{dt}=\frac{F}{m}$$ | Motion |

| Fourier's heat law | $$q=-kA\frac{dT}{dx}$$ | How heat is conducted through a material |

| Fick's law of diffusion | $$J=-D\frac{dc}{dx}$$ | Movement of particles from high to low concentration |

| Faraday's law | $$\Delta V_L = L \frac{di}{dt}$$ | Voltage drop across an inductor |

In engineering ordinary differential equation's (ODE) are very common in the thermo-fluid science's, mechanics and control systems. By now you've solve many ODE's however probably not using numerical methods. Suppose we have an initial value problem of the form

$$

\frac{dy}{dt}=f(t,y), \quad y(t_0)=y_0

$$

where $f(t,y)$ describes the rate of change of $y$ with respect to time $t$.

# Explicit Methods

## Euler's Method

Eulers method or more specifically Forwards Eulers method is one of the simplest methods for solving ODE's. The idea of the Forward Euler method is to approximate the solution curve by taking small time steps, each step moving forward along the tangent given by the slope $f(t,y)$. At each step, the method updates the solution using the formula

$$

y_{n+1} = y_n + h f(t_n, y_n)

$$

where $h$ is the chosen step size. This makes the method an **explicit method**, since the new value $y_{n+1}$ is computed directly from known quantities at step $n$. Let's try and code this in python

```python

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.style.use('seaborn-poster')

%matplotlib inline

# Define parameters

f = lambda t, s: np.exp(-t) # ODE

h = 0.1 # Step size

t = np.arange(0, 1 + h, h) # Numerical grid

s0 = -1 # Initial Condition

# Explicit Euler Method

s = np.zeros(len(t))

s[0] = s0

for i in range(0, len(t) - 1):

s[i + 1] = s[i] + h*f(t[i], s[i])

plt.figure(figsize = (12, 8))

plt.plot(t, s, 'bo--', label='Approximate')

plt.plot(t, -np.exp(-t), 'g', label='Exact')

plt.title('Approximate and Exact Solution \

for Simple ODE')

plt.xlabel('t')

plt.ylabel('f(t)')

plt.grid()

plt.legend(loc='lower right')

plt.show()

```

Although Forward Euler’s method is easy to implement and provides insight into how numerical integration works, it is not very accurate for larger step sizes and can become unstable for certain types of problems, especially stiff ODEs. Its accuracy is **first-order**, meaning the local error per step scales with $h^2$, and the global error across an interval scales with $h$. Because of this, Forward Euler is often used as a starting point for understanding numerical ODE solvers and as a baseline for comparing more advanced methods like Heun’s method or Runge–Kutta.

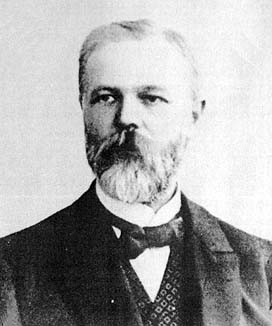

## Heun's Method

Heun’s method introduced by German Mathematician Karl Heun is a refinement of the Forward Euler method. Like Euler’s method, it starts from the initial value problem

$$

\frac{dy}{dt} = f(t, y), \quad y(t_0) = y_0

$$

The idea is to improve accuracy by not relying solely on the slope at the beginning of the interval. Instead, Heun’s method first uses Forward Euler to make a **prediction** of the next value, then computes the slope again at this predicted point, and finally averages the two slopes to make a **correction**. Mathematically, the update step is

$$

y_{n+1} = y_n + \frac{h}{2}\big[f(t_n, y_n) + f(t_{n+1}, y_n + h f(t_n, y_n))\big]

$$

This averaging of slopes makes the method **second-order accurate**, which means its global error decreases proportionally to $h^2$ rather than just $h$, as in Forward Euler.

In practice, Heun’s method provides a significant improvement in accuracy without adding much computational cost. It still only requires evaluating the function $f(t,y)$ twice per step, making it more efficient than higher-order methods like Runge–Kutta while being more stable and reliable than Forward Euler.

## Classical Runge-Kutta

Also known as the **classical fourth-order Runge–Kutta (RK4)** method. It takes four slope evaluations per step: one at the beginning, two at intermediate points, and one at the end of the step. These slopes are then combined in a weighted average to update the solution. RK4 is accurate to **fourth order**, meaning the global error scales as $h^4$, which is far more accurate than Euler or Heun for the same step size. In practice, this makes RK4 the “workhorse” of many ODE solvers where stability and accuracy are needed but the system is not excessively stiff.

**SciPy’s `solve_ivp`**, build on this idea with adaptive Runge–Kutta methods. For example, `RK45` is an adaptive solver that pairs a 4th-order method with a 5th-order method, comparing the two at each step to estimate the error. Based on this estimate, the solver adjusts the step size automatically: smaller steps in regions where the solution changes quickly, and larger steps where the solution is smooth. This makes `RK45` both efficient and robust, giving you the accuracy benefits of Runge–Kutta methods while also taking away the burden of manually choosing an appropriate step size.

## Problem 1: Exponential decay

## Problem 2: The Predator-Pray Model

## Problem 3: Swinging Pendulum

# Implicit Method

Implicit methods for solving ODEs are another numerical schemes in which the new solution value at the next time step appears on both sides of the update equation. This makes them fundamentally different from explicit methods, where the next value is computed directly from already-known quantities. While explicit methods are simple and computationally cheap per step, implicit methods generally require solving algebraic equations at every step. In exchange, implicit methods provide much greater numerical stability, especially for stiff problems. The general idea of an implicit method for a first-order ODE is to write the time-stepping update in a form such that

$$

y_{n+1} = y_n + h f(t_{n+1}, y_{n+1})\tag{2}

$$

where $h$ is the step size. Unlike explicit schemes (where $f$ is evaluated at known values $t_n$, $y_n$), here the function is evaluated at the unknown point $t_{n+1}, y_{n+1}$. This results in an equation that must be solved for $y_{n+1}$ before advancing to the next step.

Implicit methods are especially useful when dealing with stiff ODEs, where some components of the system change much faster than others. In such cases, explicit methods require extremely small time steps to remain stable, making them inefficient. Implicit schemes allow much larger time steps without losing stability, which makes them the preferred choice in fields like chemical kinetics, heat conduction, and structural dynamics with damping. Although they require more computational effort per step, they are often far more efficient overall for stiff problems.

## Backwards Eulers

The implicit counter part of Forward Euler is the Backward Euler method. Like Forward Euler, it advances the solution using a single slope estimate, but instead of using the slope at the current point, it uses the slope at the unknown future point. This creates an implicit update equation that must be solved at each step, making Backward Euler both the easiest implicit method to derive and an excellent starting point for studying implicit schemes.

## Problem 1: Chemical Kinetics

## Problem 2:

# Systems of ODE's

All methods for single ODE equations can be extended to using for system of ODEs

## Problem 1:

|